Just before 8 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, hundreds of Japanese fighter planes descended on a U.S. naval base near Honolulu, destroying or damaging 20 American naval vessels and more than 300 airplanes. A total of 2,403 Americans were killed, and another thousand wounded.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed Congress the next day, famously calling the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor “a date which will live in infamy.”

The speech not only led the U.S. to formally enter World War II, but also inspired a 21-year-old Jewish man, who was listening on the radio from southwest Baltimore, to join the U.S. Navy.

On July 4, 1942, despite his father’s reluctance, Samuel Ansel, who turned 100 in June, enlisted as a seaman, then still using the name Anselevitch.

“When you first go in, they shave your hair,” he said. “I learned it’s to make you realize you’re now under the Navy — you do what we tell you and when we tell you to do it.”

He was stationed in Norfolk, Va., where his relatives lived, in a small Jewish community, and where he brought his new wife Deborah, who was known as the “queen of the blintzes,” he said. The family would often invite Ansel’s fellow Jewish service members for dinner, as there were few kosher restaurants in the city at the time.

Although Ansel admits his memory understandably “isn’t what it used to be,” he has many stories of his time during the war and proudly recalls “mixing with a lot of different types of people” and coming within inches of death during pitch-black nights.

As an aviation mechanic, Ansel repaired airplanes and other aircraft to ready them for overseas missions, traveling to distant places like Africa, where he spent nine months.

“He learned new skills to benefit the war effort and was meticulous in carrying out all duties wherever needed,” his daughters Marsha Ansel and Fran Plotkin said in an email.

After his first tour ended, he reenlisted and continued to serve. He had passed the test to become a chief petty officer, but after nearly three-and-a-half years, he was ready to return to Baltimore. On Oct. 18, 1945, he was honorably discharged, about a month after the Japanese formally surrendered and the war officially ended.

While landlords often avoided renting to couples who were pregnant, Ansel and his wife were able to find an apartment. And the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, allowed him to matriculate at Johns Hopkins University, where he was among the 1% of Jewish undergraduates. To remain in the program, he had to maintain a high GPA.

Ansel described earning bachelor’s degrees in history and education as one of his proudest accomplishments.

“I graduated, something I never dreamed I could do,” he said. “I couldn’t have done it without my wife’s typing.”

The newly minted grad changed his last name to Ansel, making good on a promise to his brother, who’d thought it was “nuts” to keep the name Anselevitch.

Ansel went on to work in the Baltimore City Public Schools system, also receiving the equivalent of master’s and doctoral degrees. He retired 45 years ago.

“I thought I could help some kids and do some good,” he said.

In an unofficial capacity, Ansel has taught Torah, Hebrew and Jewish history to all those around him. His daughters describe him as a “man of strong beliefs and advocacy” dedicated to supporting the Jewish community in both Baltimore and Israel. He and his wife, who died in 2001, were founding members of the Randallstown Synagogue Center, which has since closed.

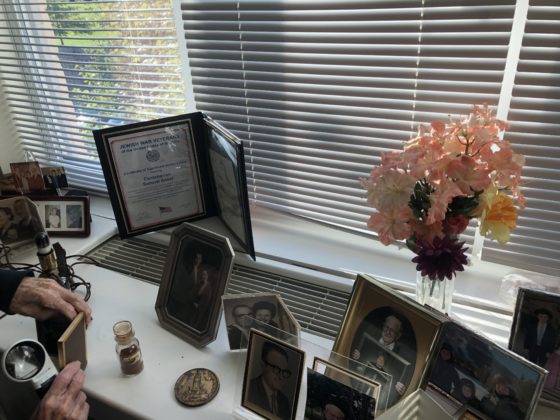

Ansel, who chose to be shomer Shabbos at a young age when his family was not, is also a lifetime member of the Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America.

Five months ago, Ansel celebrated his centennial birthday with five generations present. He has two children, three grandchildren and 13 great-grandchildren — as well as one great-great-grandchild.

Living in Owings Mills, Ansel thanks God every morning that he’s still alive. He said age-related changes are “very hard” and that he is grateful for the care he receives through the Veterans Health Administration.

To stay abreast of current events, he reads Hamodia, a daily newspaper in the Orthodox Jewish community. He also keeps up with the stock market.

His secrets to longevity? “Try not to stay aggravated” is one of them, he said.

“I didn’t drink, I didn’t smoke, I didn’t take dope and I’ve tried to be a decent person,” he said. “I daven every morning. I gathered decent people around me and tried to learn from them.”