By Jesse Berman and Chloe Sarbib

Great works of art often become so present in our everyday lives — the “Mona Lisa” on a mug, “The Starry Night” on a sweater, Basquiat in Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s Tiffany campaign — that it’s easy to forget how fragile the originals are. These images that populate our collective consciousness all started as a single destructible canvas. But most museums don’t highlight the life these artworks have had as physical objects — often because that history is wrapped up in colonialism and theft.

During the Holocaust, the Nazi regime stole millions of artistic and cultural works from across Europe, for ideological and financial reasons, and destroyed even more. While some of those surviving pieces of art have since been recovered, much of it remains missing.

“For [the Nazi regime], the arts were part of their propaganda machine,” said J. Susan Isaacs, a professor of art history at Towson University. “They disliked what they viewed as the elitism of the avant-garde and saw a way to connect that dislike to the public; it was a kind of populism.”

The story behind some of the artworks that survived the Nazis is on display at the new exhibition, “Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art,” which opened last month at the Jewish Museum in New York. The exhibit will not be traveling, but an accompanying book with the same title will be published Nov. 2 by Yale University Press in collaboration with the museum. The book will be available for purchase on the museum’s website or wherever books are sold.

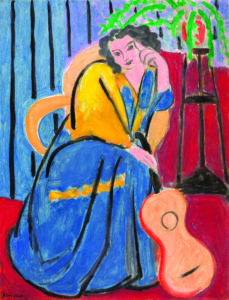

The exhibit is organized around how the artwork it features — including works by Chagall and Pissarro (both Jewish), Matisse, Picasso, Bonnard, Klee and more — came to hang there. All the pieces displayed were either directly affected or inspired by the looting and destruction of the Nazis.

“The vast and systemic pillaging of artworks during World War II, and the eventual rescue and return of many, is one of the most dramatic stories of twentieth-century art. … Artworks that withstood the immense tragedy of the war survived against extraordinary odds,” reads text on the wall at the exhibit. “Many exist today as a result of great personal risk and ingenuity.”

Motivations

Isaacs said that though the Nazis stole works of art from many different kinds of artists, Jewish ones were some of their main targets.

“They especially confiscated art from Jewish Art Collections and public museums,” said Isaacs, a former member of Congregation Beth Emeth in Wilmington, Del., in an email. “This is because controlling culture was an important aspect of running the Third Reich.”

Another major motivation for the mass theft was to amass private collections for Nazi leaders, Isaacs said. For example, some impressionist paintings on display at the Jewish Museum in New York, like Matisse’s “Girl in Yellow and Blue with Guitar,” spent the Holocaust in the personal collections of high-ranking Nazi officials — Hermann Goering in this case.

Finally, many pieces of art were sold off to fund the German war effort. The exhibit calls out these financial incentives that spurred the Nazis to steal from Jewish collectors: It was as much about seizing Jewish wealth as about any ideological beliefs.

The organized looting was so rampant that by the war’s end the Nazis had stolen about a fifth of all the art treasures in the entire world, Isaacs said.

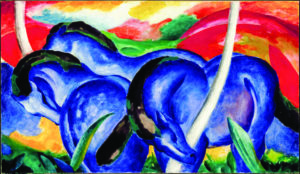

‘Degenerate’ art

The Nazis had a particular contempt for modern art, which they considered “degenerate,” Isaacs said.

Germany was in debt when the Nazis came to power, and even art labeled “degenerate” was often sold on the international market to fund the Nazi war machine if they thought it would fetch a good price.

To add insult to injury, 650 of these artworks, some of them by Jewish artists, were placed in a special exhibition that traveled throughout Germany, with the aim being not to appreciate, but rather to mock.

“The idea was to have visitors laugh and make fun of works by modern artists whose works had been collected by museums and who had taught in the art schools,” Isaacs said.

After the tour, some of these “degenerate” artworks were auctioned off, while others were destroyed, Isaacs said.

Protection and recovery

In response to this mass theft, the U.S. government formed The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program in 1943, with the goal of safeguarding cultural property during and after the war, Isaacs said.

“There were 400 service members and civilians who worked with military forces to safeguard historic and cultural monuments,” Isaacs said. “Some of them are portrayed in the 2014 film ‘The Monuments Men.’”

de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangère – La Courneuve (Jewish Museum via JTA)

That being said, there were also some Americans who took part in art theft, Isaacs stated.

One particularly striking tale of bravery the exhibit recounts is that of Rose Valland, a curator at the Jeu de Paume, which housed the work of the impressionists. During the collaborationist Vichy regime, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERR, took over the museum building. The ERR, “one of the largest Nazi art-looting task forces operating throughout occupied Europe,” used the space to store masterpieces it had taken.

Valland, who had worked at the Jeu de Paume before the war, stayed on during the Occupation and collaborated with the French Resistance to track what the Nazis did with the stolen paintings. Pieces by Jewish or modernist artists were often slated for destruction. Valland was unable to save many of them and referred to the room where they were housed as the “Room of the Martyrs.”

![Johannes Felbermeyer, Artworks in storage at the Central Collecting Point, Munich, [ca. 1945-1949]](https://www.jewishtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Holocaust-art-4-300x227.jpg)

Moving forward

When asked what lessons, if any, can be learned from this dark chapter in art history, Isaacs had a clear message.

“Employing propaganda to attack education and culture to gain power was one part of a political system that resulted in violence and destruction,” Isaacs said.

As for the curators of the “Afterlives” exhibit, they stated that many “of the artists, collectors, and descendants who owned these items are gone, and as the war recedes in time it can become even harder to grasp the traumatic events they endured. Yet through these works, and the histories that attend them, new connections to the past can be forged.”

Parts of this story originally ran on JTA.org. [email protected]