Rich Polt, a Towson resident, thinks of memories as heirlooms. He runs the company Acknowledge Media, producing legacy videos based on conversations with loved ones and layered with photos, keepsakes and music.

Some may worry that wanting to record their memories is selfish or could be perceived that way. But, according to Polt, “it’s really not that at all. It’s about safeguarding that which is most precious for a family for future generations, which is our stories about where we come from and who we are.”

While everyone should preserve their memories, Polt said, it can be particularly important for Jews.

Catholic churches, for instance, kept birth and marriage records, whereas synagogues historically did not. Many of the few records that did exist were burned or lost during pogroms and migration.

In his book “Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory,” the late Columbia University professor of Jewish history Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi notes that the commandment to remember, “zachor,” appears nearly 200 times in the Hebrew Bible: remember the covenant, remember the Sabbath, remember that you were once slaves in Egypt.

Many Jewish rituals are meant to evoke memories. On Passover, we eat matzah so that we may remember the Exodus. Similarly, in his seminal work “Remembrance of Things Past,” French-Jewish author Marcel Proust writes about being reminded of his childhood by the taste of a madeleine cake dunked in tea.

And today, remembering the Holocaust is essential to the Jewish identities of more than three-quarters of U.S. Jews, according to the most recent Pew Research Center survey.

Indeed, through millennia of diaspora and persecution, collective memory has been crucial to the continuity of the Jewish people.

“Memory is part of our Jewish DNA,” said Bruce Black, editorial director of The Jewish Writing Project. “Judaism — its stories and legends, its history and recipes, its values and even its humor — can survive only if it is handed down… from one generation to the next.”

Polt stressed the importance of what Marshall Duke, a psychology professor at Emory University, calls the “intergenerational self” — a self that is defined by one’s placement in a family history. Duke’s research suggests that the children with the most self-confidence and resilience are the ones who have a strong intergenerational self and know the ups and downs of their family narratives.

According to Robert Neimeyer, a psychology professor at the University of Memphis, we look for — and create — meaning after the death of a loved one. “A central task of grieving,” he and his colleagues wrote in a 2014 paper, “is the reconstruction of those narratives.”

Indeed, though our writing can be for family members and other readers, it can also help us as writers to make sense of our experiences and ourselves.

In 1999, two psychologists at the University of Texas at Austin, James Pennebaker and Janel Seagal, found that writing about important personal experiences in an emotional way can improve physical and mental health.

Audrey Polt, Rich Polt’s mother, said that it is valuable to write about family regardless of whether your relationships were positive or negative.

“Having those memories preserved, upon reflection, can also help you face the past with a more mature perspective, rather than avoid dealing with unresolved issues,” she said.

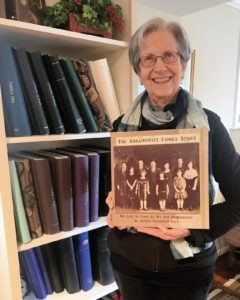

Formerly a senior consultant for Creative Memories, Audrey Polt is now an independent consultant and educator, chronicling Baltimoreans’ lives through albums of photos and stories. The shelves of her basement studio are lined with traditional scrapbook albums and digital albums, which include family histories she created in tribute to her parents.

The one for her mother, who died when Audrey Polt was in her 20s, is captioned, “We live as long as we are remembered.”

“If you leave some legacy of your thoughts and your writing, then you’re never really gone,” she said. “The people who follow you will have what you’ve left them, and they’ll carry that with them forever. It’s such a profound gift.”