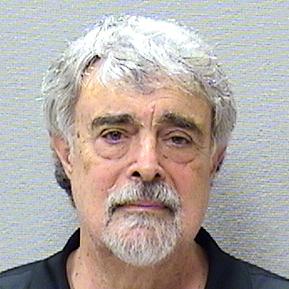

It wasn’t until Robert Sloane — now 80 and a retired Spanish professor — was about to get married at 22 that he found out that his father and his family were all Jewish.

And Eva Cockerham, 51, an immigration attorney who works in Baltimore City, found out her great-grandmother was Jewish after her mom, Margaret Green, who was adopted as a baby, began her search for her biological mother, Cecilia Saunders. Cockerham was in seventh grade when she learned of her maternal Jewish ancestry.

Sloane and Cockerham both recently spoke to the JT about their experiences finding out about their Jewish heritage.

The ancestors of both, Sloane and Cockerham, hailed from Eastern Europe — Russia for Sloane, and Russia or Latvia for Cockerham, whose maternal great-grandmother, Celia Khan, arrived in the U.S. in 1896.

Sloane is a former chair of the Modern Languages and Literatures Department at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He trained in theater at Dartmouth and upon college graduation spent a year at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts.

His father, Robert Ralph Sloane, was a well-known radio and television producer, actor and director. Born in Queens, N.Y., in 1912, Sloane’s father produced several successful shows, including “Treasury Men in Action” for television, and “Mr. and Mrs. North” for radio. He also acted in several Broadway plays from 1933 to 1935 such as “Substitute For Murder” (1935), “Ladies’ Money” (1934) and “Twentieth Century” (1932), among others.

Sloane was 12 years old when his father died of a heart attack at age 42. It was a devastating loss for a preteen boy, for his younger brother David, sister Thelma and mother Thelma, who was pregnant with Sloane’s youngest sister, Dorothy.

Sloane remembers his father as a brilliant if exacting and cautious man. And he remembers him as a man of integrity.

When he was 22, his Jewish fiancée’s parents were not happy that she was about to marry a non-Jew. When Sloane confided in his mother, he recalled her telling him, “I think I need to tell you something, which is that your father was Jewish, and he didn’t want me to tell you. He didn’t want the kids to know.”

It was a family decision, Sloane found out later, to change the family name from Solotaroff to Sloane sometime around 1913, when Sloane’s father was approximately a year old. The concern, as he understands it, was that given the prevalent antisemitism, the family would not get ahead in their chosen professions. And Sloane never met the rest of his father’s family, except for his father’s older brother, Gerard.

Sloane recalls visiting a rabbi at a college his wife attended at the time — not long after learning of his paternal Jewish heritage — to ask where he fit in Judaism. The rabbi replied, “Your mother isn’t Jewish, so you are not Jewish.”

“I thought at one point,” Sloane said, “that my name means nothing. I am not Sloane. But I was even less Solotaroff as I had no connection to this lost identity, and the Jewish communal knowledge I had was entirely secular.”

Asked whether it would have made a difference if the rabbi’s response had been different, Sloane replied, “It might have worked, to be given a sense of adventure, not something you’ve been given, but a ‘come and see where it takes you, come and see what resonates in your heart.’”

As for Cockerham, she has learned that her biological great-grandmother spoke Yiddish. When her great-grandmother arrived to the United States fleeing pogroms, she wanted to leave antisemitism — and her Jewish identity — behind.

“I do know that my great-grandmother and my great-grandfather had decided to sell everything they had so that my great-grandmother could come to the U.S. and bring their children. My great-grandfather stayed behind. They traveled in the hull of a ship. Two of their children died on the way to the U.S.,” Cockerham said.

Cockerham said that when she found out her great-grandmother was Jewish, she was young and didn’t realize the significance, adding, “I do remember that my [biological] grandmother was ashamed of it and didn’t want to talk much about it.”

For Cockerham, reclaiming that heritage was important. “I think a lot about my Jewish heritage. How the decisions of my great-grandparents and my grandmother have altered what my existence and experience could have been. I’m told that I’m considered Jewish because of the blood I have flowing through my veins. I reflect on that a good bit. I want to know more about my family and their experience. I’m proud to be a Russian Jew. I equate it with my desire to always fight the good fight and to always fight for the underdog.”