By Jan Lee

Vered Stearns was barely 5 years old by the time she had decided on her future career path. It may not be the kind of career that most 5-year-old Israeli girls dream about, but for Stearns it was a passionate decision: Becoming an oncologist would give her the tools to help people like her grandfather, who had been diagnosed with cancer.

“I have this childhood memory of spending many days and weeks in a hospital where my grandfather was hospitalized and just being so inspired by the clinical team that took care of him,” said Stearns, who belongs to Beth Am.

That experience at her grandfather’s bedside would help shape her educational pursuits years later when she moved to the United States as a young woman, as well as how she would use that training to complement a growing need at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

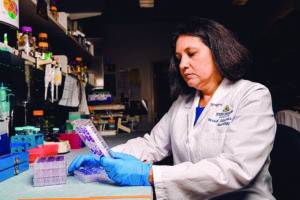

Today, Stearns is considered one of Johns Hopkins’ top experts in breast cancer, serving in a variety of roles that benefit from her clinical research skills as well as her passion for patient care. She serves as a professor in oncology at Johns Hopkins University, where she teaches and conducts research related to breast cancer. She also is the director of the Women’s Malignancies Disease Group and breast cancer research chair in oncology at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, where she plays an integral role in both cutting-edge research and treatment of breast cancer.

Stearns said it was during her fellowship training at Georgetown University that she realized the kind of oncologist she wanted to be.

“They were just incredible role models, and I wanted to be like them, to make an impact on the lives of women,” she said.

Stearns is now a role model herself for many of her colleagues and students, said Dr. Cesar Santa-Maria, who completed his fellowship at Johns Hopkins under her direction and now serves as an assistant professor in oncology.

“Beyond being a researcher, she really is a mentor and a teacher for us and in many aspects, a role model,” Santa-Maria said.

Building bridges with translational research

Today’s breast cancer treatment is worlds away from the oncological treatment options of Stearns’ grandfather’s era, when it often took years for breakthroughs in clinical research to be accepted by the medical community and to reach the bedsides of patients. A new collaborative approach, Stearns said, is helping to transform and speed up both research and treatment outcomes.

“What I always tell my patients is that yesterday’s clinical trials are today’s treatment,” she said.

And nowhere is that more evident than in the growing field of translational medical research, where practitioners, patients and researchers may all play a role in finding better ways to treat breast cancer. With TMR, doctors and scientists are able to work together to not only craft better treatment options for the particular patient but discover approaches that may one day lead to better outcomes for breast cancer patients in general.

TMR is often referred to as “bench to bed” research because it serves to “translate” the research that has been done in a laboratory to real-life treatment for the patient. Many times this is accomplished by first determining the type of breast cancer that the particular patient has (which in itself can be challenging), and then networking with laboratories to identify treatments that can target the specific cancer.

This method can have profound outcomes, not only for the individual patient, but for future advances in research and treatment, said Dr. Antonio Wolff, who serves as a professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins University and the director of Breast Cancer Trials in the Women’s Malignancies Program at the Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Translational research is not just about bringing the best ideas from the lab to the clinic,” Wolff said. “At a fundamental level it is about connecting people, and bringing individuals with diverse backgrounds and skill sets (personal and professional) to conceive, plan and execute projects. It is about trying to understand what are the barriers to conduct research, develop new evidence and translate that into action in the clinic in a manner that impact on the lives of individual patients. It is about helping patients not only survive their cancer diagnosis but also survive the impact of the disease and our treatments on their quality of life, professional lives and personal lives. It’s about seeing the bigger picture.”

For Stearns, who is able to interface with teams in multiple fields in the process, TMR opens doors.

“We have multiple collaborations with scientists across, not just the school of medicine, but also the undergraduate campus and many other entities,” she said. “As a clinical translational researcher, I meet with my colleagues to have a better understanding of their laboratory science or a novel imaging test or an assay (analysis) that they want to eventually bring to the clinic. So my job is to try to understand where they think the impact will be in the future and help decide whether we can design a clinical trial for treatment, or a correlative study of a new survey or a new [test result that is needed] to help eventually improve the outcomes of those with breast cancer.”

Treating the individual patient

An important tool that’s used for diagnosing and treatment in breast cancer these days is what is called a biomarker. In simple terms, biomarkers are indicators that can help doctors or researchers diagnose (or rule out) a particular medical condition. They may be particular proteins or other molecules found in a blood sample that are particular to a certain kind of cancer, a defective gene or a particular finding on a mammogram.

Stearns said her team frequently uses biomarkers to diagnose cancers and to help narrow treatment options that are tailored to the patient’s specific needs.

People who carry a defective BRCA gene, for example, are known to have a higher risk of breast cancer. BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes help cells repair themselves when something goes wrong while cells are dividing. A defective BRCA gene provides a biomarker, or a flag, that helps doctors determine if the patient is at risk for cancer. But biomarkers can also be used to help doctors determine the right course of treatment in cases of cancer, too.

For example, Stearns explained, in the case of patients whose breast cancer has the Her2 oncogene, the use of biomarkers and TMR can allow doctors to figure out which patients can be treated solely with anti-Her2 medications, allowing them to forgo chemotherapy in some cases.

Preventive steps are important too

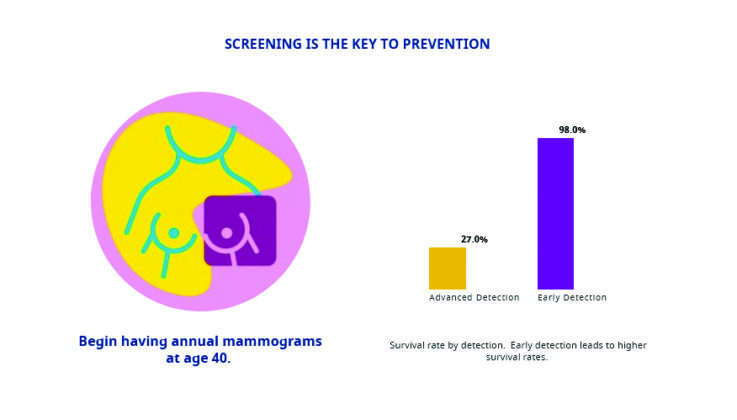

Stearns hopes that developing technology will one day also be able to prevent the onset of cancer. By identifying the unique biomarkers to a specific hereditary cancer like BRCA-1 or BRCA-2, for example, doctors could alert and monitor patients who have a higher-than-normal risk of developing the condition.

But she stressed that the first preventative step toward any type of breast cancer starts at home with good dietary choices and exercise. Doctors know, for example, that high-fat diets are associated with many types of cancer.

“We usually recommend diets that have healthy proteins in them, and those are chicken or fish,” she said.

She said she usually recommends individuals limit their red meat intake to once a week.

While researchers haven’t found a direct association between breast cancer and red-meat intake, “heart-healthy balanced diet is important to lower the risk of several types of cancer,” Stearns said.

Sugar, as well, should be on the watch list.

“[We] do know there is an association between the insulin resistance and developing cancer, similar to developing diabetes and heart disease. So, having a diet that’s relatively low sugar is reasonable,” Stearns said.

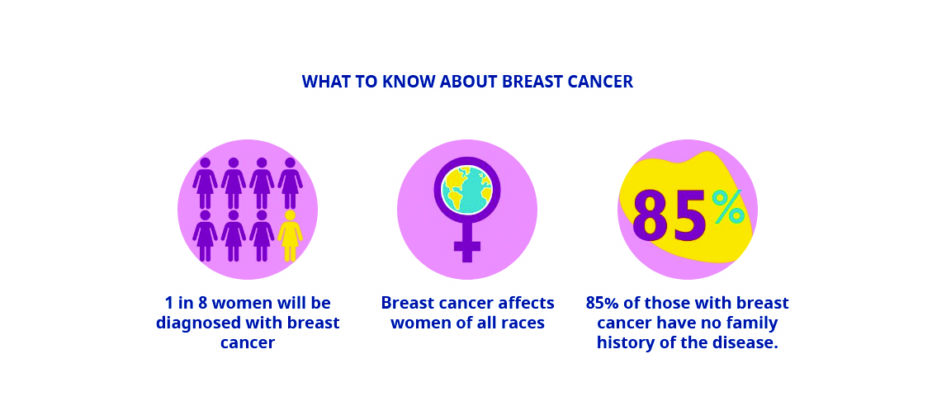

Knowing one’s family history is also an important preventative step. Women in North America have a 1 in 8 (12.5%) chance of developing breast cancer. For individuals carrying one of the two defective BRCA genes, the risk is 45-72% chance in their lifetime of developing cancer. Ashkenazi Jewish women have an even higher risk, since BRCA gene abnormalities have been found to run in Ashkenazi families. So knowing whether there’s been any breast cancer or other tumor types in your family is important, Stearns said.

She admits that limiting favorite foods and snacks can be hard. “Of course, [the] favorite Jewish foods that I cannot stay away from are fresh challah and some of the pastries. And those are fine, but in moderation.” She said she doesn’t believe in any one type of diet to best guard against cancer, but rather in balanced meal plans that focus on low-fat foods, vegetables and fruits, accompanied by regular exercise.

Jan Lee is an independent journalist living in Canada who writes on Jewish culture, history, business and the environment.